For the last 15 years, there has been an increased awareness of human trafficking in the U.S. That awareness has resulted in various federal and state laws seeking both to prevent human trafficking and protect the victims of human trafficking. See Trafficking Victims and Protection Act of 2000, 22 U.S.A. Chapter 78 (reauthorized in 2003, 2005, 2008, and 2013). Today’s post recognizes that January is National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month and discusses recent federal laws and accompanying state policy that focus on identifying and providing services to children who are in foster care and are victims of sex trafficking.

What Is Sex Trafficking?

North Carolina defines sex trafficking as part of its criminal statutes that address human trafficking and sexual servitude. Human trafficking involves a person who recruits, entices, harbors, transports, provides, or obtains by any means another person with the intent that the other person be held in involuntary or sexual servitude. G.S. 14-43.11. Sexual servitude involves “sexual activity”

- when anything of value is directly or indirectly given, promised, or received by any person whose conduct is induced or obtained by coercion or deception, or is from a minor younger than 18; or

- that is performed by any person whose conduct is induced or obtained by coercion or deception, or is from a minor younger than 18.

G.S. 14-43.10(a)(5) (see G.S. 14-190.13(5) for a list of what constitutes “sexual activity”).

Federal law defines a victim of “severe forms of human trafficking.” The federal definition includes a minor under the age of 18 who is induced to perform a commercial sex act. Similar to the NC law, fraud, force, or coercion is not required for a minor to be a trafficking victim. 22 U.S.C. § 7102(9) & (14).

In 2013, North Carolina enacted “safe harbor” laws that recognized minors (ages 17 and younger) were victims of sex trafficking. S.L. 2013-368 amended the Juvenile Code by adding to the definition of abuse human trafficking (G.S. 14-43.11), involuntary servitude (G.S. 14-43.12), or sexual servitude (G.S. 14-43.13). See G.S. 7B-101(1)g. The criminal statutes for prostitution were also amended to make it so that any person younger than 18 is immune from prosecution for prostitution. G.S. 14-203(2), –204(c). Instead, if a person who is suspected of or charged with prostitution is discovered to be a minor, law enforcement must take the minor into temporary protective custody and make a report of suspected abuse to the director of the department of social services in the county where the minor resides or is found. G.S. 14-204(c); 7B-301.

The Federal Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act, P.L. 113-183

In September 2014, Congress enacted the Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act (“The Act”). The Act seems to build on findings made by Congress in the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005 that:

- human trafficking occurs domestically as well as internationally, and

- runaway and homeless children in the U.S. were highly susceptible to being domestically trafficked in the commercial sex industry.

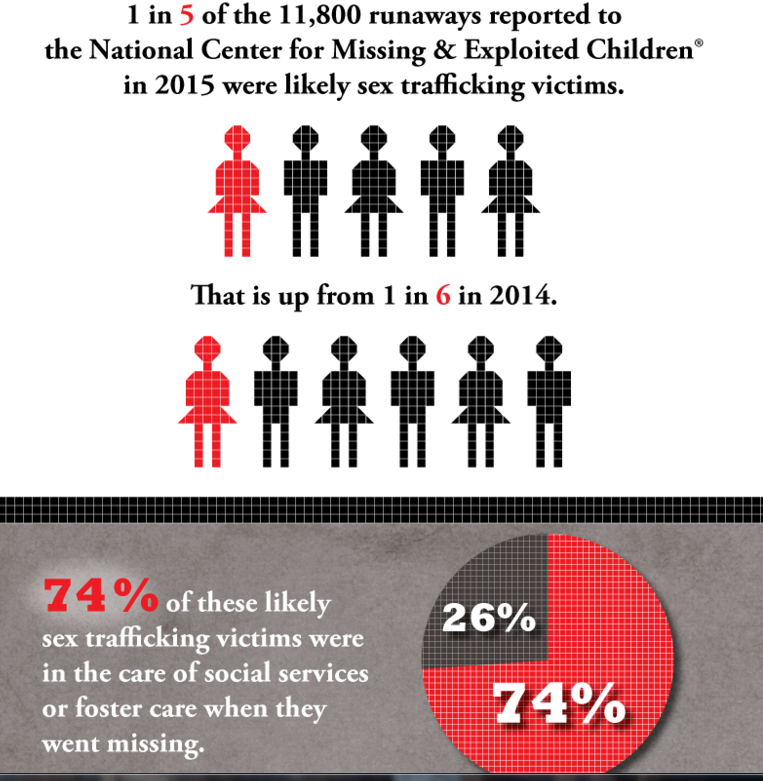

As the graphic above illustrates, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children reports that in 2015, almost 75% of the 2,360 likely sex trafficking victims were in the care of a state’s child welfare agency.

The Act requires states to focus on children in foster care who may be at risk of or are victims of sex trafficking. Specifically, The Act requires states to develop policies and procedures by September 2015 that identify, document, and determine appropriate services for children

- who were the in the state’s care or supervision, and includes those children who were the subject of a child welfare assessment but had not yet been removed from his or her home, and

- who the state has reasonable cause to believe is or is at risk of being a sex trafficking victim.

The policies should be developed in collaboration with law enforcement, juvenile justice, education, and organizations that work with at-risk children. Id. The policies must contain specific protocols to address

- expeditiously locating any child missing from foster care,

- determining the primary factors that contributed to the child being missing,

- responding to those identified factors,

- assessing the child’s experience when he or she was absent from foster care, including screening for possible sex traffic victimization, and

- requiring the child welfare agency to report to law enforcement within 24 hours of receiving information of a missing child so that law enforcement can enter the information in the FBI’s National Crime Information Center database (see also 42 U.S.C. §671(a)(34)(A)).

North Carolina’s Policy

In compliance with The Act, the NC Department of Health and Human Services Division of Social Services amended Section 1201 of its Child Welfare Service Policy Manual effective September 2015. See Section V (Out of Home Placement Services), Subsection E (Agency Plan for Abducted or Runaway Foster Children), pages 16-29. Key requirements of NC policy are as follows:

Report by Placement Provider

When a child is missing from his or her placement, NC policy requires that the placement provider (which may be a relative, foster parent, or staff at a residential facility) make an immediate report to both law enforcement and the local child welfare agency that the child is missing. The policy does not provide guidance for how a placement provider determines if a child is missing and if so what it means by “immediate.” Note that the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines immediate as without delay or now.

One may be tempted to look to NC’s Caylee’s Law, which was enacted in 2013, for guidance. See S.L. 2013-52. Caylee’s law defines the “disappearance of a child” as when a parent or person providing care or supervision for a child who is younger than 16 does not know where the child is and has not had contact with the child for 24 hours. G.S. 14-318.5. Under Caylee’s law, a child’s disappearance must be reported to law enforcement, and a parent’s or person’s who supervises the child wanton and knowing failure to make a report is a Class I felony. Id.

Caylee’s law is narrower than the NC policy. The NC policy applies to all children who the county department is legally responsible for. This includes teens who are 16 and 17 years old. In addition, a child in care may be missing before 24 hours passes. A placement provider should use his or her best judgment to determine if the child is missing based on the specific facts and circumstances (i.e., child’s age, the child’s history of running away) that exist. There is no set number of hours that must pass before a provider determines that a child is missing. As soon as a provider believes the child is missing, he or she should call the police and child welfare agency. By making a report to the police, the placement provider is complying with both NC policy and Caylee’s law.

Report by Child Welfare Agency to Law Enforcement

NC policy requires the department case worker to immediately notify law enforcement after the case worker learns the child for whom the agency is responsible is missing. The case worker must also provide written notification to law enforcement within 48 hours. NC policy designates what information about the child the case worker should share with law enforcement, much of which is aimed to assist law enforcement in locating the child. The case worker should also report to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). NC policy explicitly states information sharing is not a violation of any confidentiality laws. Information provided to law enforcement and the NCMEC is specifically authorized by G.S. 7B-302(a1)(1), which allows the department to share confidential information with a federal, state, or local agency to protect a juvenile.

Expeditiously Locating a Missing Child

NC policy requires the case worker to also notify the child’s family (unless familial abduction is the suspected reason for the child being missing) and the child’s court appointed guardian ad litem so that they can work together to try to locate the child. Efforts to locate the child should be collaborative and involve law enforcement. Note that the policy does not address what action law enforcement is required to take.

The case worker must notify his or her supervisor and meet regularly with him or her. If the child is high risk, the meetings must take place daily; otherwise, they may occur weekly. High risk is defined by NC policy as when a missing child’s safety is severely compromised because of an identified factor, such as the child has been a victim of human trafficking, is pregnant, is drug dependent, has a health condition requiring daily treatment, etc. See page 17 of Section 1201.V.E of the policy. The purpose of the case worker – supervisor meetings is to ensure the case worker is complying with the policy mandates and to assist the case worker in developing and implementing a plan to locate the child. The plan should be amended as needed. Placement considerations for when the child is located should also be discussed.

Motion with the Court

NC policy requires the case worker to file a motion with the court within 10-14 business days of when the child has been reported missing. Although the policy states the case worker must file the motion, the motion should be filed by the department’s attorney, who has entered an appearance in the juvenile action. Note that the policy mandates the filing of a motion, but there has not been an accompanying statutory change requiring such a motion. Despite the absence of statutory language, any party may file a motion for review with the court in an abuse, neglect, and dependency proceeding. See G.S. 7B-506, -906.1, -1000. The purpose of the motion is to inform the court of the child’s status and the efforts being made to locate the child (if the child has not been found by the date of the court hearing). The hearing should address placement options for the juvenile, especially if the juvenile ran away from his or her current placement, and services the juvenile will require. The court is authorized by the Juvenile Code to order services for the child and an appropriate placement that the court finds is in the child’s best interests. G.S. 7B-903.

Next Steps:

The General Assembly may want to consider legislation that codifies the requirements of The Act, including provisions that have been created by NC policy, such as the requirement to make a report about a missing child in foster care or the need for a judicial review when a child has been missing from his or her placement. Training for child welfare case workers on the issue of sex trafficking and children in foster care is required by the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act of 2015, P.L. 114-22. Current and former foster youth who have an adjudication or conviction of prostitution from when they were minors may want to petition the court for expunction of the offense from their records pursuant to G.S. 15A-145.6. For information about the expunction process, see my colleague’s, John Rubin’s, Guide to Relief from a Criminal Conviction, Discharge and Dismissal or Conviction of Prostitution Offense.

*the introductory graphic is from www.missingkids.com/1in5